I, We and Change: How belonging can make our break your change initiative.

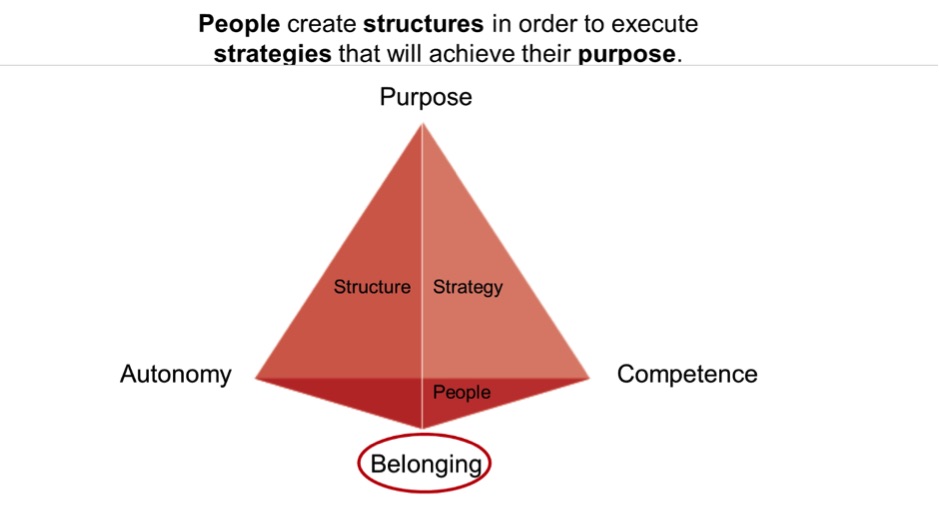

In my book, ”The Human Way – The Ten Commandments for (Im)Perfect Leaders” I present the following model which describes the most important building blocks of the individual’s motivation and the group’s ability to perform at a high level. The presidential election has affected and been affected by all of these components. The American people are clearly not in agreement about a common purpose for our country or our political direction. Many people don’t feel a sense of autonomy believing that their opinions or their votes don’t matter. Less than half of the American voters showed up at the polls and of the ones that did vote many are disillusioned and dissatisfied with the political process. I may be entering dangerous territory, but, as voters, our competence has a significant impact on our ability to understand important issues and choose the right candidate.

In my book, ”The Human Way – The Ten Commandments for (Im)Perfect Leaders” I present the following model which describes the most important building blocks of the individual’s motivation and the group’s ability to perform at a high level. The presidential election has affected and been affected by all of these components. The American people are clearly not in agreement about a common purpose for our country or our political direction. Many people don’t feel a sense of autonomy believing that their opinions or their votes don’t matter. Less than half of the American voters showed up at the polls and of the ones that did vote many are disillusioned and dissatisfied with the political process. I may be entering dangerous territory, but, as voters, our competence has a significant impact on our ability to understand important issues and choose the right candidate.

As I thought about the election from a change management perspective I began to realize that one factor, “belonging”, had a more significant impact on the election than any of the others. The way we perceive our sense of belonging or lack thereof has a significant impact on change and has played a decisive role in this presidential election.

Who is ”we”?

Almost exactly 4 months ago I woke up in a hotel room in London to discover that the UK had just voted to leave the EU. Yesterday, I woke to the news that my homeland, the USA, had just elected Donald Trump to be the next president. Both of these events surprised and shocked me. There are many parallels between Brexit and the election of Trump but at the heart of these two movements is a strong need by the voters to clarify who “We” is. We live in a global world where local, state or national boundaries are becoming less important in areas like communication, trade, entertainment, manufacturing, purchasing, education and much more. But we also live in a time where millions of people have been driven from their homes by war or by the effects of climate change. These changes have threatened many people’s understanding of ”We”. Who are “We” in this new world?

These questions cut to the heart of our need for a sense of belonging and belonging is all about trust. The fact that I can trust the group, that we watch out for each other’s interests, and share responsibility for the well-being of the group, is fundamental to my ability to survive in a world full of dangers and threats. Can I trust people from other places who look differently and have other habits and values? If the old definition of “We” changes, what is my role in the “We”. Will I have the same power and influence as before? Will I get by as well as I did before?

Those of you who have heard me speak or attended one of my courses have probably heard me say that ”your company is only make-believe. It doesn’t matter if you work for Volvo, Microsoft, or Disney, your company doesn’t really exist”. I usually go on to explain that the same thing is true for municipalities and government agencies. The fact is that the USA, Sweden and the UK are all make-believe too, just like all the other countries in the world. Corporations, government agencies, and countries are all fictions that people have created to simplify or facilitate the workings of society. There isn’t really a border between the USA and Canada. We have just agreed to “pretend” that there is a line between these two parts of what is otherwise the same land mass. In the same way my neighbor and I have agreed to pretend that there is a border between my yard and his.

”An enterprise (or operation) is where people cooperate of their own free will to achieve common goals or a shared purpose.”

When we register a corporation, we become the owners of a “legal entity”. A legal entity is not a ”real” person. What characterizes an enterprise is that people choose to cooperate towards a shared purpose or common goals, not the fictional structures that we human beings create. When we have initiated an enterprise, in other words, begun a cooperation between people to achieve common goals or purpose, we create structures like property lines, country borders, corporations and much more to help us achieve what we set out to do. Over time, we create symbols, like logos, flags, clothing styles, language and more which also help us to achieve our purpose.

In my work, I get the opportunity to peek inside and get to know many different organizations. One thing I notice immediately upon coming into a new organization is that they almost all have their own jargon. I often have to ask someone to back up and explain what they mean by ABK, GAS, or DAP. This is an example of how a group begins creating their own language or at least their own dialect in order to create a more efficient communication. This behavior also has the added benefit of helping to identify the ”We”, in other words, who is in the group and who is not. The same tendencies develop with clothing styles and other social signals.

The same things occur in a country. As an old English colony, English became the main language of the USA. With time, the United States developed its own dialect of the English language and with even more time, numerous American dialects emerged. You can recognize an American by their dialect. Or can you? Sometimes these social signals that help us define our “We” can get confusing. I often hear young people in Sweden speaking fantastic English with an American accent. Similarly, despite the fact that I am an American, I have developed a Swedish accent when I speak English after having lived in Sweden for more than 30 years. (It is a bit of a paradox that I sound Swedish when I speak English and I sound American when I speak Swedish.)

So what is the problem?

Major changes in society that threaten our understanding of who “We” are create an understandable counter-reaction by many people. It is tempting to grasp even harder to those unique characteristics that defined the old ”We”. One expression of this is the increased nationalism we see in many countries. According to Dictionary.com, nationalism, the policy or doctrine of asserting the interests of one’s own nation viewed as separate from the interests of other nations or the common interests of all nations. Nationalism is a worldview that has its starting point in a sense of belonging defined by national borders. Nationalism hails the nation, its culture, and its history as something that defines a commonality between a group. In other words, nationalism is a way of defining who “We” are. The term ”nation” can be traced to the latin ”natio” or birth,and originally referred to a group of people who were born in the same place. The term later developed to have roughly the same meaning as state or country.

One of the main problems with this worldview is that the “nation” or country doesn’t really exist. Nations are fictions, created by people to help us achieve our goals and/or fulfill our purposes. But what often happens in both countries and organizations is that the fictions we have created to help us achieve our purpose become more important than the purposes they were created to achieve. People can fight to retain their tools and symbols long after they have stopped filling any real purpose. A new work process that was developed many years ago to help solve a specific challenge in our organization can be virtually impossible to change despite the original problem no longer existing. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t mean to imply that fictions like nations, corporations, money, or other human inventions aren’t important, they can be very important. But they are only important as tools, not as a purpose in themselves.

Most modern organizations are much larger and more complex than what is revealed by looking at organization diagrams or who is on the payroll. What characterizes an organization is not who is on the payroll, it is all the people who cooperate to contribute to the organization’s common goals and purpose. Consultants, outsourcing partners, customers, and many others can be a part of the “real” organization even though none of them are formally employees. For example, as a citizen of the USA, I benefit from the same rights and am bound by the same responsibilities whether I actually live in the USA or not. For most countries, citizenship is not solely defined by geography. Similarly, you can be an American or a Swede without being born in those countries and maybe not even legally a “citizen”. What makes a person Swedish or American is the same thing that makes people part of your business organization; that they contribute to your common goals or purpose. Over time these people will create their own expressions of belonging. They will develop common language in the form of words, expressions, acronyms and symbols. They will adapt to each others’ ideas and habits and create new ones together. At some point this new sense of belonging will be challenged and changed again.

It is important that we keep our focus on the purpose of our structures and symbols. Why did we create these fictions? What did we want to achieve with them? When our fictions no longer contribute to achieving our purposes we can eliminate them. At first glance you might think that the purpose of a soccer match or a football game is to make as many points as possible. But you don’t necessarily have to make lots of points to win, all you have to do is make one more point that your competitor. A team could become world champions if they always only make one point more than their opponents. And was the purpose of the game really to win? Or was it to have fun, or stay in shape, or for entertainment? The fact that we create games with winners and losers may simply be a fiction that we create for excitement and entertainment.

We need to keep our focus on our purpose and that purpose is the same in all sound organizations, to create a better world. Freedom, our right and need to control our own destinies, to participate in the management of our country or our place of employment is an important principle. This freedom creates autonomy and contributes to well-being, security, stability, increased productivity and ultimately to a better world. Our organizations, like countries and businesses, are important tools to help us create a better world but they are not the goal in themselves. If you look at a list of the companies that were most important for society 100 years ago you will find that not many of them still exist. In the same way, the map of the world is constantly changing. Country borders change, countries disappear and new ones are created, some merge together and others split apart. These lines in the sand are important as long as they contribute to creating a better world and when they no longer serve that purpose we can draw new lines in the sand. These changes can be costly and painful but they are necessary.

- Define the purpose of the organization. (In what way is the world better, or will be better because we exist?) (Sometimes it is actually better to ask how the world would be worse if we didn’t exist.)

- Be clear about the purpose of your change initiatives.

- Communicate how these changes contribute to your organization's purpose.

- Differentiate between the purpose of the organization and the resources and structural tools we create to realize the purpose.

- Take a long-term perspective. Creating a better world, society, organization, or a better life for you as an individual is not a linear process. Improvement goes up and down. With skill, hard work, and a little luck, when the development curve goes up, it goes a little higher than it did the last time and when the curve goes down it won’t go quite as low as it did before.