Tools to help you succeed with change management

Change manangement in a nutshell

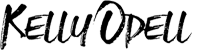

Here is a graphic I created to give a quick overview of several tools for change and how they all fit together. I call it the “Change Management Storyboard”

Success factors for change

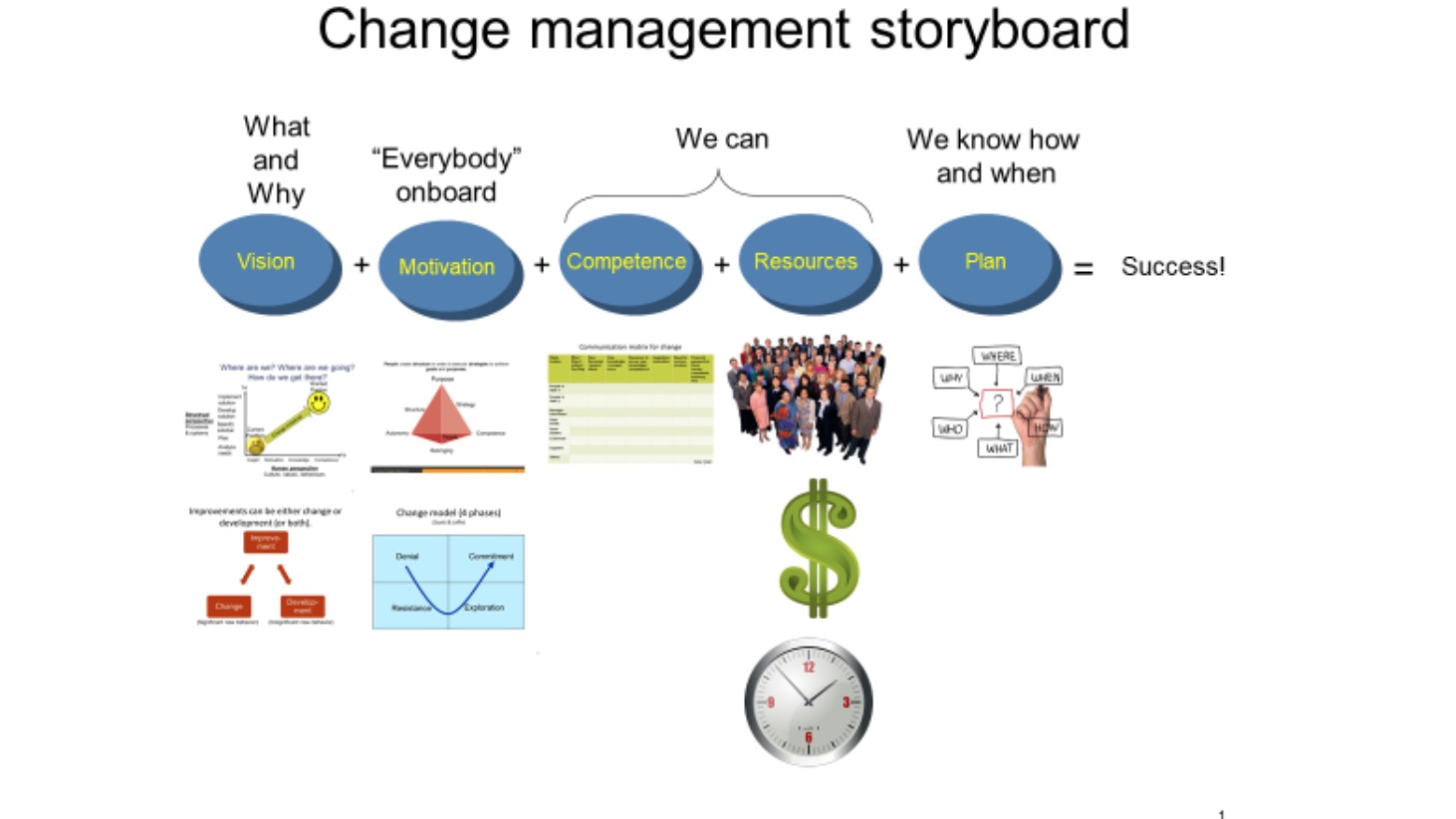

The following graphic begins with a proven model that describes the factors for successful change. The model shows that if we have a vision for the change, the motivation for the change, the skills to cope with/perform the new behavior, the required resources for the change and a good plan, then we can succeed making the change. The model also shows the typical symptoms that occur in the organization if any of the factors should be missing. (It is difficult to be completely sure of the source of this model. It is clear that the model goes back at least 30–40 years, perhaps even longer. Several older sources suggest that it may be from an American technology company called Raytheon).

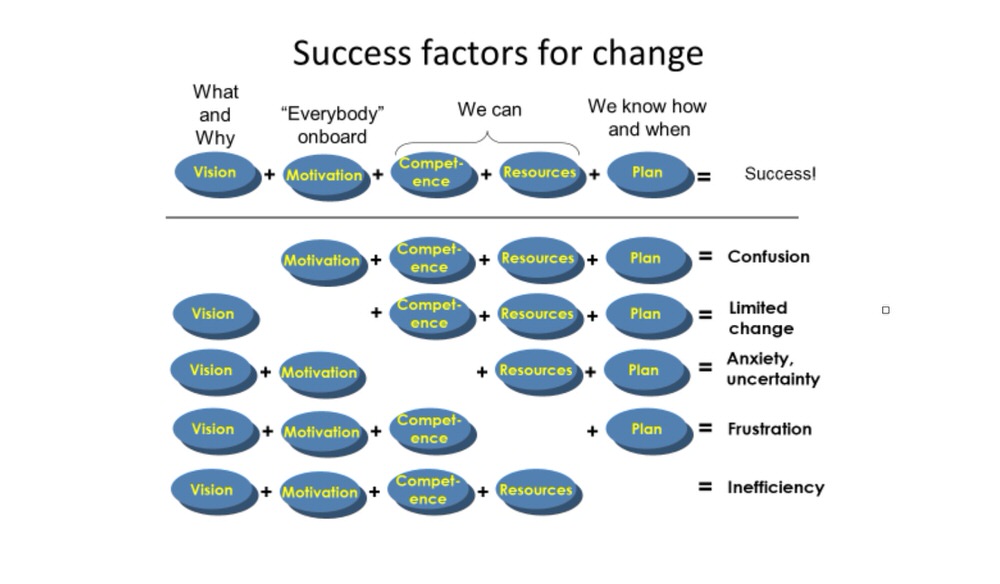

Where are we, where are we going, and how will we get there?

The “vision“ for the change paints a picture in which the future is better than the present. This vision for the future requires changes in the behavior of many people in order to realize the improved situation. I usually say that the change vision should describe “how the world will be better when we have succeeded with the change.” The term “world” may refer to an individual department, a business unit or a division of the business, the entire organization, or perhaps the community at large. We should be able to describe the change vision in terms of a concrete improvement for someone somewhere. If we cannot describe how the change creates a real improvement we should probably not implement change.

Change always requires changing behaviors. From a change management perspective this is precisely the definition of change. If an improvement doesn’t require significant behavioral change it is not a change. I divide improvements into two categories, those that don’t require significant behavioral change (Development) and those that do (Change). For example, changing all the servers in your server hall could be an enormous project involving a large number of people and create a major improvement in the performance of your IT environment but it would likely not require any significant change in behavior by your people or your customers and would therefore not qualify as a “change”. But if you then implemented a new IT system that required training and significantly changed the way the people in the organization work that would be an example of a change initiative.

Stop trying to motivate people, inspire them instead