The secret of motivation

Some time ago I had a speaking engagement at a kickoff for a large company. I was asked to speak to a large group of employees for an hour about” Living with Change”. This company, like most, was driving several major change initiatives. Before I was to take the stage, there was another well-known speaker who was going to hold a motivational speech. If you have ever been to what I often call a ”hallelujah” kickoff then you would probably recognize this type of speaker. He ran back and forth across the stage and told the audience that ”everything is possible” and that they could achieve “150%”. He told them about his own very personal challenges in life and how he succeeded in overcoming them and said that if he could succeed then they could too! Despite the fact that his speech was entertaining, I couldn’t help but think that I could probably write a book about all the things he stated as “truths” that research has shown to be false. In fact, in my book “The Human Way” I have included a chapter on “Myths about organizations and the people in them” to address some of the more common “truths” that have turned out not to be so true.

Some time ago I had a speaking engagement at a kickoff for a large company. I was asked to speak to a large group of employees for an hour about” Living with Change”. This company, like most, was driving several major change initiatives. Before I was to take the stage, there was another well-known speaker who was going to hold a motivational speech. If you have ever been to what I often call a ”hallelujah” kickoff then you would probably recognize this type of speaker. He ran back and forth across the stage and told the audience that ”everything is possible” and that they could achieve “150%”. He told them about his own very personal challenges in life and how he succeeded in overcoming them and said that if he could succeed then they could too! Despite the fact that his speech was entertaining, I couldn’t help but think that I could probably write a book about all the things he stated as “truths” that research has shown to be false. In fact, in my book “The Human Way” I have included a chapter on “Myths about organizations and the people in them” to address some of the more common “truths” that have turned out not to be so true.

I have often attended this kind of kickoff event, sometimes as an employee in the audience and sometimes as the manager who has initiated the event for my subordinates. I have also frequently been that” motivational speaker” tasked with the job of motivating the audience. If you have been to a kickoff like this you may have had the same experience I have had, you may come home from the event feeling less motivated than you were when you went there. When I have organized similar events for my employees I have sometimes had the feeling that my employees motivation was at best unchanged but in the worst case their motivation was lower than before. But why was this happening?

Knowledge that created a change

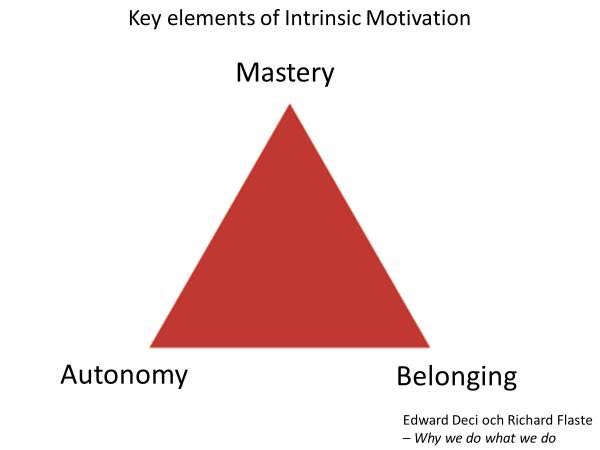

One day about 15 years ago, I found a book that in some ways changed my life. At any rate, it changed the way I viewed my role as a manager and as an employee. The book was” Why We Do What We Do: Understanding Self-Motivation by Edward Deci, a psychology professor, and Richard Flaste, a Pulitzer prizing-winning science journalist. Deci and Flaste realized that despite the fact that researchers learned much about motivation, very little of this knowledge had been put to practical use in our daily lives. Most managers I meet believe that motivating their employees is one of their most important tasks. In fact, most employees I meet also believe that their managers should motivate them. But Deci and Flaste tell us that the research on motivation indicates that it is extremely difficult and impractical to motivate other people. Their advice to those of us who find ourselves in leadership roles is instead of asking how we can motivate people, we should be asking: “How can we create the conditions within which people will motivate themselves?”

Create a motivational climate

It is all about creating an environment where people can express their motivation. According to Deci and Flaste, studies have identified two types of motivation – intrinsic and extrinsic – and each affects us differently.

Intrinsic motivation is a drive to do something, or to achieve something, and we all have that drive inside us. Intrinsic motivation entails doing something to satisfy that inner urge. To quote Deci and Flaste: “Smelling the roses, being enthralled by how the pieces of a puzzle fit together, seeing the sunlight as it dances in the clouds, feeling the thrill of reaching a mountain summit: these are experiences that need yield nothing more to be fully justified.” Intrinsic motivation occurs whenever the activity or behavior is a reward in itself, and although there may be other rewards involved, it is not these other rewards that generate the motivation.

Extrinsic motivation involves the drive to do something that offers some type of external reward, such as a bonus, commissions, a kickoff, or a grading system. Intrinsic motivation is, at best, not influenced by external motivational factors such as a new bonus or commission system or a sales kickoff to entice everyone to work harder, and at worst, these external factors can be inhibiting.

The secret lies in aligning the interests of the people with the interests of the organization. If these interests are not aligned, motivation will drop. In an ideal situation where all employees work with things they are genuinely interested in, work with other people who have similar interests and who share a common purpose and goals, motivation will take care of itself. But reality isn’t perfect, far from all employees (or managers for that matter) have chosen their profession and their place of work based on their passions and interests. Even those who have initially chosen their professions based on their intrinsic motivation can find themselves in situations where managers or organizational cultures take the joy out of work. I usually tell managers to stop trying to motivate their employees and instead start inspiring them.

If you can’t motivate yourself, no one else can motivate you either

Let your employees take responsibility for their own motivation just as you as a manager take responsibility for yours. The single most significant contribution you can make to your own motivation at work is to choose the right job. If you have chosen or fallen into a job that you don’t enjoy, it won’t matter how good your boss is at motivation. And if you have chosen the right job, your boss will have to be pretty bad before you will stop enjoying your work. Make sure you have chosen the right job, at the right place, so you can be intrinsically motivated (or at least taking the necessary steps to get to that job). Then you can start helping other people to find their motivation.

As a leader, you can create opportunities for people to satisfy their intrinsic motivations by inspiring them. You can plant seeds, awaken ideas, thoughts and questions, but it is the individual themselves who must decide what to do with these inspirations. It may seem to be a marginal difference between motivation and inspiration but the difference is significant. The individual is responsible for their own motivation while inspiration can come from many sources. And we can all be inspired by things that we aren’t motivated to do anything about.

I often ask my audiences to try and imagine a man in his fifties who hates his job. The fact is that he has hated his job for 25 years but he gets up every morning, clinches his fist, locks his jaw and goes to that “damn job”. When the day is over he comes home from that “damn job”. He has been doing this for 25 years. I hope that there aren’t any people like my made-up person in real life, but if there are, they have no lack of motivation. It would require an enormous amount of motivation to drag yourself back and forth to a job you hate for 25 years. The problem here is not a lack of motivation, the problem is that my fictional character is not motivated for his work.

Three Key Elements for Intrinsic Motivation

Edward Deci and his colleague R.M. Ryan identified three key elements of Intrinsic Motivation. Competence, autonomy (self-determination) and relatedness (sense of belonging) are the cornerstones of motivation. If I, as a manager, wanted to help a colleague find an outlet for his or her work motivation, I would consider how I could help them to improve their skills or competence. Employees who feel they are not very good at their jobs do not feel any strong motivation, while those who have mastered their jobs find it satisfying and are motivated to do more. A manager can boost an employee’s competence in various ways, including introducing education, on-the-job training, and other opportunities for development. As the skills of an employee increase in relation to their work duties, so will their motivation. Bear in mind that the manager, in this instance, does not create motivation in his or her employees. The manager simply ensures that staff have the right conditions under which to find an outlet for motivation within their work. The other two corners of the triangle are more convoluted, which is the result of our own complexity. On the one hand, we want a high degree of self-determination – none of us thinks it is particularly inspiring to be controlled or to have others interfering in how we perform our roles. On the other hand, we want to feel part of the group. I have met many managers who have expressed their frustration at not knowing how much freedom they should give their staff to increase their level of self-determination and to what extent they should monitor people, to ensure they comply with company work methods and rules. In today’s companies, we invest a great deal of energy in charting, developing and implementing standardized processes and work procedures. The question is: can you create a high degree of autonomy without crippling the company’s standardized work procedures? I would argue that you definitely can!

Create your own goals

When I was in charge of sales for Volvo Cars I was given a budget which said how many cars we had to sell and how much money we should make. But instead of dividing up the budget among my subordinate regional managers and giving them a directive, regarding set targets, I told them about the goals of the budget I had received and asked them: “Can you divide up the budget between yourselves and come up with a plan on how we can deliver it?” I left them to work it out in peace and the regional managers later presented their joint proposal, which was not far off from the one I would have drawn up. The difference was that I did not come up with the proposal, they did. Naturally, their motivation to achieve the goals was much greater because they had been involved in setting them. Even though my superiors had acted in a way that might diminish my sense of autonomy, this did not mean I had to act in a similar way towards the people I managed.

When employees have greater autonomy, with the freedom to set their own goals and develop their own plans for achieving these goals, they feel a greater sense of belonging and feel that they are an important part of the organization. Nothing creates a greater sense of alienation from the group than knowing that their ideas and points of view don’t really matter. This is typical in top-down organizations where employees are simply expected to execute the tasks they have been assigned and achieve the goals they have been given. In these organizations, there is no room for comments, adjustments or alternative goals or solutions. This results in employees who feel unappreciated and lack loyalty to their employers. In the case I described with Volvo, where the regional managers had greater influence over their goals and tasks, they felt greater intrinsic motivation, and that was reflected in the results.

Tips to help you motivate yourself and inspire others:

Be honest with yourself about what you want and why you have chosen the work you do.

Encourage others to either create the job they want to have or to change it.

Stop trying to motivate other people. Inspire them and help the to be driven by their own intrinsic motivation.

Invest time and money in your employees competence, increase their autonomy and get them more deeply involved in the life of the organization.

If you are not passionate about what you are doing, go do something you are passionate about.